Seven Days on a Bike

July 10, 2015

When I dragged my bike, still in its hastily loaded box, from the Greyhound station to the motel where Kayla had checked in several hours before, I was greeted by the same explosion of clothing and gear I was used to in the aftermath of backpacking trips. Kayla had a 700 mile head start in getting used to bike touring, and I was riding on enthusiasm and a few instructional YouTube videos.

I’m sure I was the picture of inexperience as I excitedly laid out my gear, bragged about the super-dense 400 calorie 1in2 brick “bars” I was sure I would love, and quietly tried to figure out how to reattach the pedals I had so painfully removed to stuff my poor bike into the confusingly narrow bike box that I had shoved under the Greyhound bus that had gotten me to our meeting point and the start of my trip. Meanwhile, Kayla dried out her things to get ready for her home stretch. Her experience and my enthusiasm made us a fantastic duo for our 320-mile, 7 day adventure.

We typically biked 40-50 miles a day, which left plenty of time for ice cream breaks, redwood-investigations, tiny-town history museum visiting, or river-swimming. On the first day, I literally started dancing and singing “gonna bike along a river, dada daDA” during our first water/bar/map-looking break. Kayla, already on day 13 of her journey, was more restrained in her river-excitement. Kayla was already sore from her solo section, I was on my first bike trip and learning everything, and we both wanted to take the time to enjoy as much California as we could.

Occasionally, our experience gap, and my pride, made communication difficult. By the afternoon of day two, my legs protested strongly for the first several minutes after every break. I started pushing for longer and longer stops, but Kayla, looking at the map, would say, “How about another five miles?” I would agree between water-chugs, without looking at the map. As the day wore on we would do the planning while pedaling, and I would bravely proclaim, raspily, that I was up for it if she was. We passed our “easy target” campsite while it was still light. After a long break and a chat with a ranger who assured us the last leg “wasn’t that bad” (I now note that she wasn’t a biker herself and may have been thinking the route wasn’t that bad in a car), we decided it would be a good idea to add 15 miles to our easy 30 mile day in the 1.5 hours before dark.

It turns out I didn’t really understand how long another fifteen uphill miles would be tacked onto our already full day. Unlike hiking, where twilight means headlights come out and you continue with a little more care than before (and if you’re in the White Mountains, you’re rewarded by the sight of glimmering mica on the trail), we would be relying on our headlamp-sized lights to alert the cars you would be sharing a highway with of your presence. Kayla, who understood the risks of an after-dark ride on the 101, was doing everything short of circling back and pacing me to keep us moving. As you can imagine, we were deliriously happy when we stagger-rolled into camp, and somehow decided giggling and tent-pole fencing needed to be part of our camp setup procedure, even though we were entering an already silent campground of cyclists who had arrived at reasonable hours.

I was surprised by how quickly we felt part of a community. Every night we camped (mostly at state parks) and would see the same crew we had been travelling with, the 40-50 mi/day crew. Once we had seen the same group for several evenings, we started checking in with each other, discussed any bike trouble we had (it is amazing what other people know!), and eventually exchanged contact information and end-of-trip victory selfies. I hadn’t expected to care for strangers we met on the road, but we found ourselves making sure we said goodbye in the morning and talking about who we might see again as we approached camp each night.

People doing more than our 40-50 miles per day might be asleep by the time we rolled into camp at 7, 8, or 9pm and be out and enjoying the empty road by 5am. One group that took this approach was a gaggle of men my grandfather’s age who were, much to my amazement, doing seventy miles a day. By the time I woke up, they were loading up their gear and teasing each other. All of us had spent most of the night trying not to hear the car camping crew that had stayed up late, getting so drunk they thought screaming would be a fun addition to their camping trip. These hardcore old men, who the night before had been the picture of polite, helpful, more experienced cyclists, now joked that they would be loud and rude as they passed the car-camping section, which, in my why-were-people-yelling morning grogginess, was an image I enjoyed thoroughly. They gave their bikes one last look, took off their fuzzy, patterned grandpa sweaters (they had full racing gear underneath), and headed out before I could brush my teeth. After meeting them, I decided that one day I would start my own sweater-clad gang of touring cyclists.

Throughout the trip, drivers were friendly, which was a relief. The first day, when the burst of turbulent air from a passing semi threw my balance a little for a few seconds after entering the 101, I realized, with that dull well-this-is-what-we’re-dealing-with shock, that if a car were to hit me at highway speed, I would probably die. The awareness stuck with me, but I felt more confident as I went, especially after I saw how many people were willing to follow behind a bike on bridges (etc.) without being consumed by rage. The fact that the route we were on is used by many cyclists meant cars were aware that we would be there and that we would be slow and vulnerable. For every expletive I heard there were at least ten thumbs up, short “hello” honks, and even the occasional peace sign. Thank you for the upvotes on those hills, California!

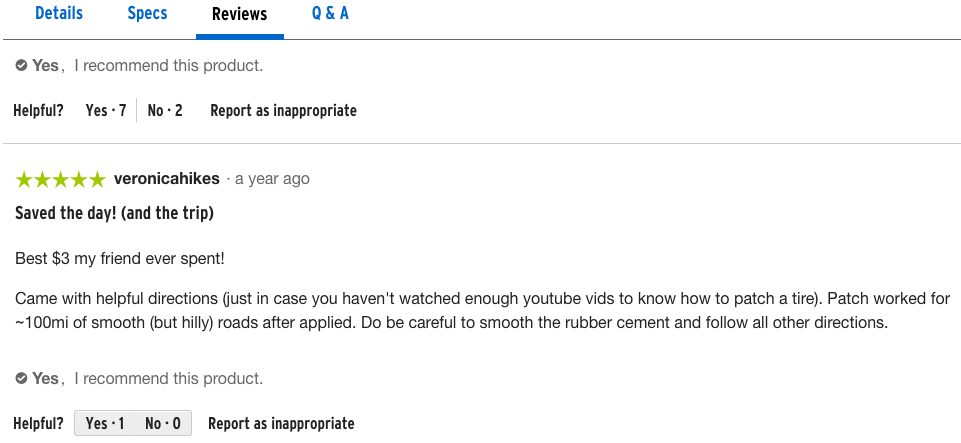

One thing I’ve come to appreciate about adventures is that you are able to deal with and experience whatever is in front of you, without the choice of “switching gears” and backloading the problem. About twenty miles into my first day, I got my first flat. Kayla hadn’t gotten a flat in the first 650+ miles of the trip, so her flat-changing memories were old and fuzzy. I had watched a YouTube video on bike maintenance after I started riding in 2009. We jumped in and started changing, occasionally saying things like “so I take off the tire…?” each time trying to swallow that we had trailed off into a question. Things got even more complicated when we realized my spare was the wrong width for my tire. Rats. I wish I had been more careful. We talked about going back to the bike shop in the town we had passed five miles before, but we were on top of a hill and neither wanted to backtrack just to get ourselves ride-ready and be staring up at the hill again. So we patched on the side of the road, waving on the occasional car. At some point in all of this, I joked “on the bright side, think about how confident we’ll feel after this.” And it’s true: I wasn’t scared of flats and knew I could trust my patch kit (well, Kayla’s patch kit) after that. Only because I’d had to. And I bought two tubes of the correct size the next chance I got. Because yeesh.

I'm now telling the world how great Kayla's patch kit was.

While I’m pretty comfortable outdoors, most of my experience is hiking, and there were many lessons for me as a hiker-turning-cyclist, the most important: take only what you need. For me, it was best for me to pack the way I would pack for the trail and then try to halve it, since I’m a confident hiker and comfortable that I can take the extra weight of a few extra comfort items, but shaky on a bike. To decide what can be left behind, think of your route, your weather, what consumables will make you happy (for me, q-tips help an otherwise dirty me feel much cleaner), and what you can re-wear. Habits die hard, so I insisted on bringing the wag-bag (used for cleanliness in dig-a-hole bathroom situations) that I had gotten so used to relying on, which doesn’t make any sense when you are traveling through towns every twenty miles or so. The sanitizer and baby wipes helped keep us clean when bathrooms were sans soap, but the toilet paper I thought I would be grateful for was just along for the ride. Very well-traveled toilet paper.

The fact that Kayla and I had nothing to prove to each other (I learned to mellow out real quick) made us less stressed when things went wrong, and we laughed about the hard parts, even as they were happening. As a bonus, now that our legs have fully recovered, we can look back and chorkle like old friends about that one map-misread which added several miles at the end of a long day and the many times my bike decided it needed some extra attention.

There was, in fact, a lot to laugh about. On the way up one particularly long, steep, shoulder-less section, I toppled into the ditch. To this day, I’m not exactly sure how that happened. But don’t worry, it was the perfect place to fall; the ditch was steep, but the weeds were thick enough that they were quite springy. I assume my front tire hit the edge of the road, but I was too tired to realize it when it happened; in fact, my only memory of the moments before the before the fall was thinking about how tired/hungry/etc. I was. Kayla would later say that from her perspective, twenty feet behind me, I had toppled smoothly into the ditch, like I was taking a dive into the waist-high weeds. As I began to pick the burrs off of myself, I teased that this was my way of declaring a break.

I spoke up more when I was tired after that, and we laughed about the time I had tried to take a nap (or maybe hide from her, that hill, and the miles ahead) for the rest of the trip. Of course, the story wasn’t quite over: the next day (before I could fully deburr) we did a grocery run and an old man in a Safeway asked, as he stood behind me in line, if I had an infestation of bugs on my shirt. I told him they were burrs and picked one off to show him. What else can you do when someone asks if you had walked into a grocery store with hundreds of bugs crawling on you? More comedy than expected came from that one little “nap.”

Even though the personal lessons were, for me, the most memorable part of the trip, the scenery, and the fact that it changed every day gave a sense of awe and grandeur that’s pretty hard to describe, but I’ll share a few of my favorite sights.

The first day was all dairy farms and sheep. It was calf time, and the little cows with their hella-big eyes were adorable. In my start-of-trip-excitement, I rode alongside my friend and told her about the types of fencing, irrigation, and weeds I remembered from my childhood. I started to wish I had a camera strapped to my head because (a) I wasn’t going to stop for a picture of a cow but (b) no one would believe me if I told them how cute they were. Trust me, the cows were adorable. In fact, farms are actually quite beautiful if you don’t immediately think of the fences you need to mend, horse poop you need to shovel, acres you need to till, etc. as you approach them.

There were redwoods, which were green and towering and shade. One of the towns we drove through had “Flats” in it’s name, so I was extra happy to be starting on this stretch. Businesses in this area often had a person-sized, twisted branch placed near their entrance, which was strange both because what makes the branches twist is a fungus (so they are displaying the beauty of what is really a sick tree) and because there are so many living trees around that the branding was less impressive.

The biggest hill we encountered, Everett, was made even more memorable by the condition of my bike during our hours-long ascent. I had noticed my tire wall budging that morning, but there wasn’t much I could do but brake gently and listen for the change in road-tire noise that I had read would come before a blowout. There were small shoulders, tight curves, and log-laden semi trucks, and I thought several times that there wasn’t enough calmness in my entire being to stay always-alert and still push forward. By the end of the day, the bulge was bad enough that it had pushed the tire out of alignment and the wheel rubbed with every turn. I have never been so happy to have a long downhill end.

Touring with a good friend had one important advantage for me, as a new cyclist: when I was in a situation that made me afraid, I felt stronger knowing that one of my best friends was the one muddling through with me. This meant that when I realized that my slightly askew tire had worn to the point that a small bulge had emerged on its side, Kayla and I decided how to handle the situation together. We continued down the hill, where the next town was, at our prefered paces, but she stopped and waited for me frequently, which made me feel much safer. We did made it up and down the mega-hill that stood between us and the bike shop, my heart continued beating, and the bulge on the side of my tire stayed small enough that it could be measured in quarter widths instead of fists and - more importantly - it didn’t interfere with the brakes. Even better, I knew my friend had been looking out for me when I had to focus narrowly on staying in control of my bike with only gentle nudges on the brakes. My confidence in both of us doubled as I soared, much too fast, down and towards the town.

Finally, we could see the coast. We stopped for many selfies and started biking slower to take everything, and with good reason: The area surrounding Rockport looked like a tourism site for New Zealand. We stopped by a tiny convenience store whose windows seemed to be the happening place to post announcements (they have both Zumba(!) and a bridge club), job notices (several hand-made signs announced that someone had a lawn blower (or similar) and wants to remove leaves (or help move things, or anything, really) for $), and political cartoons/information (an entire window was devoted to an ink-jet printed list of what had been accomplished during Obama’s presidency). The leftward lean surprised me coming from the wall of a small-town convenience store.

There were many small things we saw that were even more beautiful, because we didn’t expect them to be there: the decorative fence that modeled a large chain but was made out of connected wooden boxes, the hawk that came out of the steep hill along the road and took flight no more than ten feet from me, the blackberries that seemed to always be in the steepest parts, on the sharpest curves, where we weren’t going to stop, but were awesome anyway.

We saw farms, forests, hills, ocean, more ocean, hills near ocean, and some of the most interesting towns I have ever been through along our route. I decided at some point that, if it didn’t exist, I wanted to make a timelapse tool for a GoPro (or similar) camera especially for bike tours. Although nothing will beat the striking surprises you get along the way, the feeling of starting the day in flat farmland and ending near the ocean, day after day, is an experience so amazing that I want to be able to share the experience, with it’s ups, downs, exuberance, and mishaps with the next enthusiastic, inexperienced aspiring bike-adventurer.